Reflections on the Representation of Mark Twain and Slavery along the Mississippi

The Researching Self: Expectations.

In the course of the summer semester, cultural research methodology as well as self-awareness as researchers was repeatedly stressed and important subjects in class, since these two premises constituted the very basis of this whole experience. The fact that each of us have prejudices or 'fore-meanings' (Johnson 2004, 44) about our subjects of cultural research and that we need to be aware of our own traditions, and subject positions, was our group's starting point.

This reflection on ourselves and our personal expectations was a surprisingly uncomplicated process in terms of our first object of research Mark Twain, but turned out to be all the more difficult and challenging with regard to the second: slavery.

In terms of Mark Twain, it became quite obvious very quickly that we all had different backgrounds of knowledge about the author and his life and works. While Hubertus turned out to be a Mark Twain expert, who has been continuously doing research on the author for his thesis, Angela had read several of his works in the course of her studies, and Thekla had not really come across any of his books during her academic life, but had only been familiar with children's adaptations of Mark Twain's most popular works The Adventures of Tom Sawyer and Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.

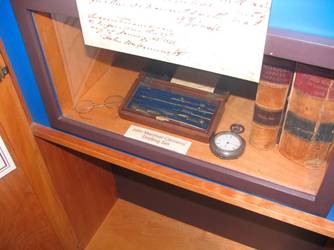

Although we all were well aware of the fact that the Mississippi - the real as well as the imaginary river - was a very influential and shaping factor for the works of Mark Twain, we came to the conclusion that we did not have any specific expectations as far as the representation of Mark Twain in the places in the Missisissippi Valley we were about to visit was concerned. We expected, however, mainly due to the information received in class, that especially in Hannibal we would most definitely be able to observe to the most extent the cultural representation, production and consumption of Mark Twain's life and work, which in the end - and not very surprisingly - turned out to be true. Apart from that, we anticipated a strong literary focus in the representation of Mark Twain, as well as a frequent use of his most famous quotations. Hubertus, having the most detailed biographical background knowledge about Samuel Langhorne Clemens, also expected a focus on the author's 'real' biography, which contains several sad and tragic instances, that are not very well known to the public, as they are often omitted in popular representations and productions of Twain's life and work.

As mentioned before, clarification of our expectations and our fore-meanings in terms of the representation of slavery and the treatment of this precarious subject in the places we were going to visit, was much more challenging. We agreed on the notion that this is a dark chapter of American history which - we assumed - the nation, and especially the American south - still has to process and come to terms with. Comparisons were made with the Second World War and how these events are still part of German and Austrian identities nowadays.

We first of all had to reflect on how we as researchers from Austria and Germany were shaped by the events of our past and concluded that there is an undeniable feeling of guilt and the awareness of the necessity to react to this feeling by treating this subject as respectfully as possible. All of us - as probably most middle European students have dealt with the events of World War II very extensively in school. It is a chapter of history we know a lot about and numerous exhibitions on that subject and trips to concentration camps have created a thorough knowledge and vivid picture of the inhumane and cruel treatment of numerous groups of people at that time. We have to live with the notion that our ancestors were responsible for these crimes. It seemed therefore very interesting for us to have the chance to observe how a different nation is coping with a troubled past to which we as Europeans only have a rather distanced relationship.

2. Section on Mark Twain (Hubertus Weyer)

Imagine you look through a microscope to examine an archeological sample and imagine that you suddenly realize that neither the microscope nor the archeological sample are real because both are made of artificially produced plastic. Would that mean that what you were looking at a moment ago is untrue? The answer to this depends on the ambiguous line between truth and untruth. Does the plastic microscope simulate a real microscope? And where does the original of the plastic sample under the plastic microscope come from? While the plastic microscope simulates a real microscope, the plastic version of the archeological sample appears to be a copy of something for which there is no original. The French philosopher Jean Baudrillard would call the plastic version of the archeological sample a simulacrum because it shows something that is true although the sample itself is not only not an original but a reproduced copy without an original. Again, the plastic microscope and the plastic sample are only artificial reproductions and yet they show the truth.

What does all this have to do with the representation of Mark Twain as we experienced it on our trip along the Mississippi from July 24 to August 14, 2010? The answer begins with our visit to Hannibal, Missouri where Mark Twain grew up. A tour of the Mark Twain Boyhood Home and Museum begins when you walk through a door on which it says: Interpretive Center.

Immediately one wonders about the difference between the terms museum and interpretative center. From an academic point of view, it is tenable to say that there is a plethora of clear biographical data about the life of Mark Twain. Although some of the literary works as for instance Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

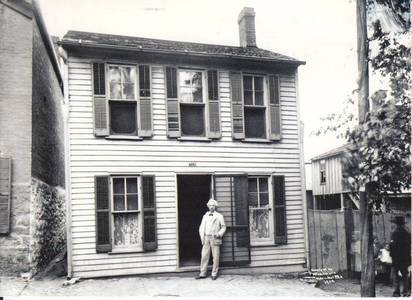

Looking at the history of the Mark Twain Boyhood Home and Museum it becomes clear that the seemingly preserved buildings are mostly not original buildings, but rather restored structures. The picture below shows Mark Twain in 1902 in front of his boyhood home, but the house that we visited on July 28, 2010 has been renovated and restored several times as is stated on the website of the Mark Twain Boyhood Home and Museum:

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer can clearly be considered autobiographical, visitors fictionally relive chapter 2 of The Adventures of Tom Sawyer when they whitewash the fence:

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer. Although several characters of the novels Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and The Adventures of Tom Sawyer

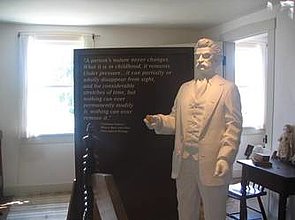

These sculptures are simulacra because the original Mark Twain is not alive any more. The portrayal of Mark Twain in white suits through the sculptures as well as the impersonator might be questioned but it has to be duly noted that the website of the museum states that Mark Twain wore white suits on several occasions rather late in life for effect but that the constant portrayal in white suits throughout his life is rather not representative.

The Mark Twain impersonator whose performance we attended can be considered a simulacrum not only because Mark Twain died 100 years ago but because Mark Twain probably never said many of the things that the impersonator said. From this point of view the impersonator is a copy without an original.

The writer Mark Twain clearly speaks when the impersonator mentions Thomas Edison since Twain and Edison really knew each other. When the impersonator talks about how the education system imposes limits on students at the end of the video excerpt, one may be under the impression that the impersonator himself voices his opinion. In sum, the excerpt shows that impersonator impersonates the fictional characters Huck Finn and Tom Sawyer, Samuel Clemens and the writer Mark Twain as well as the impersonator himself. Obviously, the separation between copy and original is very unclear. Nonetheless, the impersonator as a simulacrum conveys an impression of Mark Twain that can be regarded as generally true.

The sensitive topic of slavery in the household of the Clemens family is addressed by a rug on which slaves slept:

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn as a literary statement about slavery. In this connection one could even dare to speculate if fiction can be regarded as a simulacrum because fiction is necessarily removed from its origin. Similarly, fiction has always had to battle the question of its truthfulness if one thinks the numerous analyses in literature about fact and fiction. The approach that the interpretive center at the Boyhood Museum offers is certainly very significant in this context.

It is also noteworthy that the Boyhood Museum does not stress the literary works of Mark Twain overly much. A raft from which a movie version of Huck Finn can be watched is an example of this approach. Topics like violence or slavery are subdued by a concentration on the romanticised popular images of Tom Sawyer and Huck Finn. The stir that the publication of the first volume of a newly edited version of the Autobiography of Mark Twain has created very clearly indicates that there is a lot of interest for Mark Twain as writer and questions concerning his literary work like for instance racial aspects in Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

When thinking about the representation of slavery as an aspect of American History, a European visitor (especially a German one) comes in close contact with European history and, in this connection, first and foremost, with the incidents during the two World Wars and the consequences drawn from these horrifying chapters.

As Germans, we all had, as well as our Austrian friends, expected a certain openness and a self-critical attitude, as well as unbiased views on slavery. We had expected the same process of memorizing, which we knew from our own experiences with regard to these chapters in Europe's history.

Well, our expectations had to meet our tour guide's positionality, and her identification with the subject on this behalf.

We, as Europeans felt, that this chapter in American history had to be treated with the most of objectivity possible, in order to show respect to the numerous victims of a very cruel chapter in American history and we clearly want to state here that respect was shown to them.

But, on the behalf of our expectations, we might have been the victims of the first step of Intercultural Learning.

Ethnozentrismus

We did not have direct prejudices on the American process of memorizing right from the beginnings we were confronted with our own positionality towards the techniques of memorizing again and again on the trip.

First impression: The National Civil Rights Museum in Memphis/Tennessee

We were firstly confronted with our own thoughts and our own relationship towards slavery in Memphis/Tennessee, when we visited the National Civil Rights Museum.

The tour was not guided, we were only given an introductory documentary on the lives of Afro-Americans in the 1950s/1960s.

In terms of cultural studies, we were confronted with the question of how to position ourselves as Europeans towards a rather American aspect of history. In comparison to our American travelers, Curtis, Kaylynn and Professor Conley, who felt uncomfortable and well-aware of the mischief that had been produced by white Americans, we compared the events during this long period to the outcomes of the first and second World War. For us as Europeans, who have been sensitized on memorizing the two wars from the very beginning of our lives as pupils and students, we compared the representation of this event in history to the representations we are used to back in Europe, especially in Germany.

Controversial views on slavery at Frogmore Plantation and in the Natchez Museum of African American Culture

We then drove to Natchez/Mississippi and over to Frogmore Plantation in the State of Louisiana, where we met Mrs. Tanner, one of the descendants of the plantation- and slave-owner.

Mrs. Tanner positioned herself, due to her family's personal history, in the best possible light, which for her, was a matter of identity. She identified herself and her family with a certain image of slavery, which she conveyed to us as her consumers. In order to convince us of her position, she used material, such as pieces of literature and personal stories, proving that her version of slavery was 'the most objective one'.

We then drove back to Natchez/Mississippi-hometown of famous Richard Wright - where we met, on the same day the director of the Natchez Museum of African American Culture - an Afro-American historian himself. We were shown a very controversial perspective of the subject. In comparison to Mrs. Tanner, the historian did not romanticize slavery at all. He gave a historically more accurate version of the subject. But again, for him even more with regard to his own ethnicity, it was a matter of identity and positionality. We felt that his representation of the subject was much more authentic, than the one we had been given at Frogmore, but we were left with the question whether it is actually possible to present such a cruelty without taking sides.

As we were able to compare the two 'versions' of 'slavery' now, nearly all of us had troubles believing the version we had been given at Frogmore.

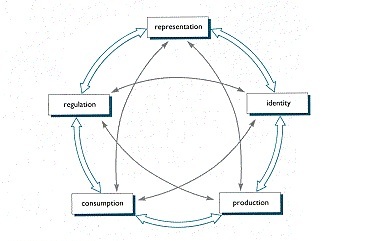

In our discussion-groups, we lively discussed the subject and it became more and more clear that there are different possibilities of memorizing, depending on one's own positionality and one's own identity. With regard to duGay's Circuit of Culture, where all processes [...] continually overlap and intertwine in complex and contigent ways [...] we now were not able to simply consume the interpretations, which we had been given, anymore.

We were told that the captured ones had one day off per week (Sundays) and even had holidays - which, after asking our tour guide Mrs. Tanner a bit further, turned out to have been 2 days per year. This privilege, we were told, was very rare during this epoch.

Another image of slavery: New Orleans

Finding the most objective point of view on this behalf became even more complicated, when were guided around the French Quarter in New Orleans a couple of days later.

Randy, our tour guide, a very lively and vivid person, added to our impression again another point of view.

From him, we learned that slaves even were allowed to earn money and buy themselves free. After having done so, they even could educate themselves and free other slaves with their own money. He provided us with another positive image of slavery in the State of Louisiana and shifted the cruelties to other Southern states as Kentucky and Georgia.

Reflexions on the three images of slavery

In the end, we were confronted with three versions of a very cruel chapter in American history and had a hard time positioning ourselves towards the subject. Johnson states that there is no objectivity in culture. 3 approaches to cultural analysis are given:

the empirical one, the interpretative one and the critical one. Each one's analysis is interwoven with the analyzer's positionality towards the subject. Hence, objectivity is not possible.

When we flew back to Europe, we very much felt that from all three side the image of slavery is constructed by identity and positionality and we still have troubles with that. We were left with these interpretations and are still in the process of asking ourselves, whether our position as Europeans, evaluating an aspect of American history and American culture, can be as objective as we would want it to be.

Mark Twain Impersonator (Video Download)

List of References

Critical Literature:

Fellner, Astrid and Klaus Heissenberger and Tim Conley, eds. Course Reader. Rafting the Web 2.0 with Huck Finn, Transatlantic Dialogues on the Mississippi Valley as a Transregional Space. Saarbruecken: Saarland University, 2010.

Baudrillard, Jean. Simulacra and Simulation. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2008.

Campell Neil and Alasdair Kean. American Cultural Studies. Routledge: New York, 2006.

Mark Twain Boyhood Museum:

http://www.marktwainmuseum.org/

Pictures:

All pictures were taken on August 28 unless noted otherwise.

Videos from the August 3, 2010

New Autobiography of Mark Twain:

Smith, Harriet Elinor, ed. Autobiography of Mark Twain: Volume I. University of California Press, 2010.

, New York Times November 19, 2010.

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/11/20/books/20twain.html?_r=1&scp=4&sq=Mark%20Twain&st=cse

Barnes and Noble discussion of Mark Twain:

http://www.newsweek.com/2010/07/30/excerpt-from-the-autobiography-of-mark-twain.html